How very important it is when chaos threatens, to draw an inflatable, portable territory. If need be, I’ll put my territory on my own body. I’ll territorialize my body: the house of the tortoise, the hermitage of the crab, but also tattoos that makes the body a territory.

Deleuze and Guattari, “A thousand Plateaus”, Trans Brian Massumi, (Continuum International Publishing Group, 2004), 353.

The purpose of these series of essays is to explore the notion of territory in relation to the state, nomads, sustainability, and art. To question how the qualities and mechanisms of territory are constructed.

Human constructions of territory vary hugely between cultures. Within a Western colonial framework territory has historically been marked by the raising of flags and other formal declarations. However such acts don’t necessarily imply the possession of land. Lasting ownership has more traditionally been established through occupation, seen as the original mode of acquisition. Such claims of ownership relied on a belief that no pre-existing title was present. This assumption was in fact the basis on which Australia was colonised. This assertion of terra nullius was famously overturned in the landmark Mabo native title determinations of the early 1990s.

Aboriginal, specifically Central Desert Aboriginal, constructions of territory and ownership of land differs greatly from those who attempted to colonise it. A senior traditional owner from the Amata community once described the state as a big eagle hovering in the sky watching Aboriginal people, and attacking whenever prey was exposed.

For Central Desert Aboriginal people, the relationship with the land, and animals is based on interdependence and reciprocity. This connection can be seen clearly in their artwork. Most artists attempt in their work to map out in paint the geography of their dreaming, country, animals, and ancestral beings that link to the Tjukurpa.

Kungkarangkalpa, or Seven Sisters, a Tjukurpa which weaves far across the country, is a prime example of how relationships between human, animal, and the land is conceptualised within Aboriginal Central Desert culture.

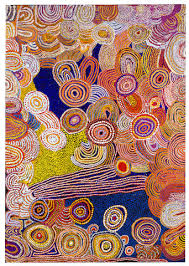

Tim Acker and Edwina Circuitt, in regards to Warakuna artists, explains that “Kungkarangkalpa Tjukurpa operates as a kind of Rosetta stone for the development of Warakurna women’s acrylic language”.(1) The collaborative painting by Carol Golding, Nancy Nyanyarna Jackson, Pirrmangka Napanangka, Eunice Yunurupa Porter, titled Kungkarangkalpa Tjukurrpa is an example of artists sharing the same Tjukurpa.

The canvas (213.03 x 151.92 cm in size) features a series of overlapping and interlaced dotted roundels and concentric circles, creating shapes and patterns that depict rock formations, trees and human movements. Painted on a black based-coated canvas the central spine of the work is noticeably looser compositionally (the dotting less compacted) than the tightly packed interlaced roundels framing the plane. The lower third of the picture plane features a stretch of dotted parallel lines, likely suggesting either tracks, sand hills or possibly even a shooting star (as the lines appear to come forth strong concentric circles.)

Vibrant earthy oranges, warm yellows and whites dominate the canvas. A flood of deep blue hue dotted in solid blocks in two areas gives the impression of the night sky, a galaxy of stars. The canvas is noticeably a collaborative work, with the hands of several different artists clearly present. The painting and the Tjukurpa it depicts represents constant transformations, into trees, animals, land formations and ultimately stars. The painting, in a way, is mapping of the in between, the interconnectedness on many levels of artists painting together on one canvas.

Elizabeth Grosz in her engagement with Central Desert art takes Kathleen Petyarre’s work, thorny devil dreaming, as an example of “story involves a typical conjunction of territory and animal, of animal traversing territory, of territory inscribed by animal movements and the qualities and sensation capable of being released through their coupling”.(2)

Grosz argues that in Petyarre’s work there is no separation between the land and the events that occur within it, whether naturally occurring or made by human design. The land is shaped by events that occur on it, and also affects them.(3)

It is through Aboriginal people’s connection to the land that they also envisage their relationship to the their community, family, to their law and culture. Thus a territory in this context is always starts from a shared space, or in other words, territory constructed within the space in between. It’s constructed within the relationships and interconnectedness with the land and other humans, not within separation.

1 John Carty with Edwina Circuitt, 2012. Warakurna Artists. In: Tim Acker and John Carty. eds. ‘Ngaanyatjarra: Art of the Lands’, (UWA Publishing. Perth, 2012), 194-195

2 Grosz, Elizabeth. ‘Chaos,Territory, Art: Deleuze and the Framing of the Earth’, (Columbia University Press. New York, 2008), 93

3 Ibid., 96.

By: Ahmed Adam

Founder and Editor of TheTerritoryInBetween